Each year 26th April is designated as ‘ Save the Frog Day’. This article is in celebration of frogs in our vicinity.

Those who grew up in cities like Bangalore until the early 1990s will be filled with vivid memories of the cacophony of frogs during monsoons. In fact, most cities have supported an average of 15-20 species of frogs, be it Bangalore, Pune or Pondicherry. Those nights would be filled with an orchestra as incessant as the rain itself. Frogs were commonplace; one would encounter them all over the courtyard, hopping behind unwary insects and making a meal of them. All one had to do was step out of the house on a rainy night, to immerse themselves in the world of frogs. Over the last decade, however, this has changed; neither are the rains incessant nor the frogs. Frogs appear to have lost the race in our quest for developed and urbanised set-ups we call ‘cities’. They are extremely rare and are restricted to the outer limits of cities, where a few tracts of un-modified habitats exist.

Toads are frogs, and frogs are considered to be the first four-legged vertebrates to have stepped on land about 360 million years ago. The earliest amphibian (Triadobatrachus sp.) evolved from a fish-like organism stepping out of water. The number of species increased between 300-250 million years ago. From then on, they have evolved to a diversity of shapes and characteristics. They are all ectotherms and dependent on atmospheric temperature and moisture availability. Slight atmospheric changes can have profound impacts on them. They are often considered barometers of the environment.

Bi-coloured Frog (Hylarana curtipes)

The earliest documentation of frogs in Bangalore pegs its diversity at 17 species (Karthikeyan 1999). These include frogs like the Bi-coloured Frog (Hylarana curtipes), which lives in streams and riparian habitats in the forests of South India; the Common Tree Frog (Polypedates maculatus) which lives in marshy areas and often turns up behind photo frames and curtains inside houses; two species of skittering frogs – the Common Skittering Frog (Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis) and Common Pond Frog (Euphlyctis hexadactyla) which are known to float over water; the rough-skinned toads – Common Toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) and Ferguson’s Toad (Duttaphrynus scaber), mostly found near human habitations and courtyards.

Common Pond Frog (Euphlyctis hexadactyla)

Common Toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus)

Two species of bullfrogs – the Indian Bullfrog (Hoplobatrachus tigerinus) and Jerdon’s Bullfrog (Hoplobatrachus crassus) were common but faced a severe threat from overharvesting for lab dissections; the burrowing frogs – Indian Burrowing Frog (Sphaerotheca breviceps) and Roland’s Burrowing Frog (Sphaerotheca rolandae), have strong hind limbs and bury backwards into moist soil, and commonly occur near gardens and lake beds.

Indian Burrowing Frog (Sphaerotheca breviceps)

Roland’s Burrowing Frog (Sphaerotheca rolandae)

Four species of narrow-mouthed frogs, Painted Frog (Kaloula taprobanica), Variegated Ramanella Frog (Ramanella variegata), Ornate Narrow-Mouthed Frog (Microhyla ornata) and Red Narrow-mouthed Frog (Microhyla rubra), have low body profiles and mostly eat ants and termites that occur commonly around water-logged areas. The Wrinkled Frog (Fejervarya caparata) occurs in wet, paddy field-like habitats and lawns; lastly, two species of balloon frogs – The Indian Balloon Frog (Uperodon globulosus) and Marbled Balloon Frog (Uperodon systoma), burrow into the soil and have a puffed up appearance.

Variegated Ramanella Frog (Ramanella variegata)

Ornate Narrow-mouthed Frog (Microhyla ornata)

Red Narrow-mouthed Frog (Microhyla rubra)

The swansong of frogs

Frogs may have seen dinosaurs come and go. But today, amphibians in general are severely threatened by human activities. World-over, amphibian declines are being reported. The home range, dispersal ability, body size, life-history strategy, and tolerance of frogs to variation in precipitation and ambient temperature are some of the inter-connected factors that have been identified and broadly categorised into ‘threat drivers’ and ‘decline drivers’. While threat drivers jeopardise the existence of a species, decline drivers result in large-scale declines in populations (Bickford et al. 2010).

Each species has its own habitat requirements and limitations on how far it could move in search of it. Small puddles in vacant land, fountain tanks in gardens, and large lakes once found commonly in cities, were perfect frog habitats. With increasing human population, there is less space in the hearts and minds of people for smaller animals like frogs. Rapid urbanisation is a continuous process where wilderness areas are converted to residential and industrial layouts. Even the small puddles and slushy areas in and around our homes have completely become concretised and maximised to accommodate the burgeoning number of people. Agricultural areas near cities are converted to human dwellings and natural wetlands away from cities are converted to agricultural land in order to feed the masses. With the loss and fragmentation of habitats, frogs are unable to move into other habitats. Moreover, with habitats being lost everywhere, frogs have nowhere to go.

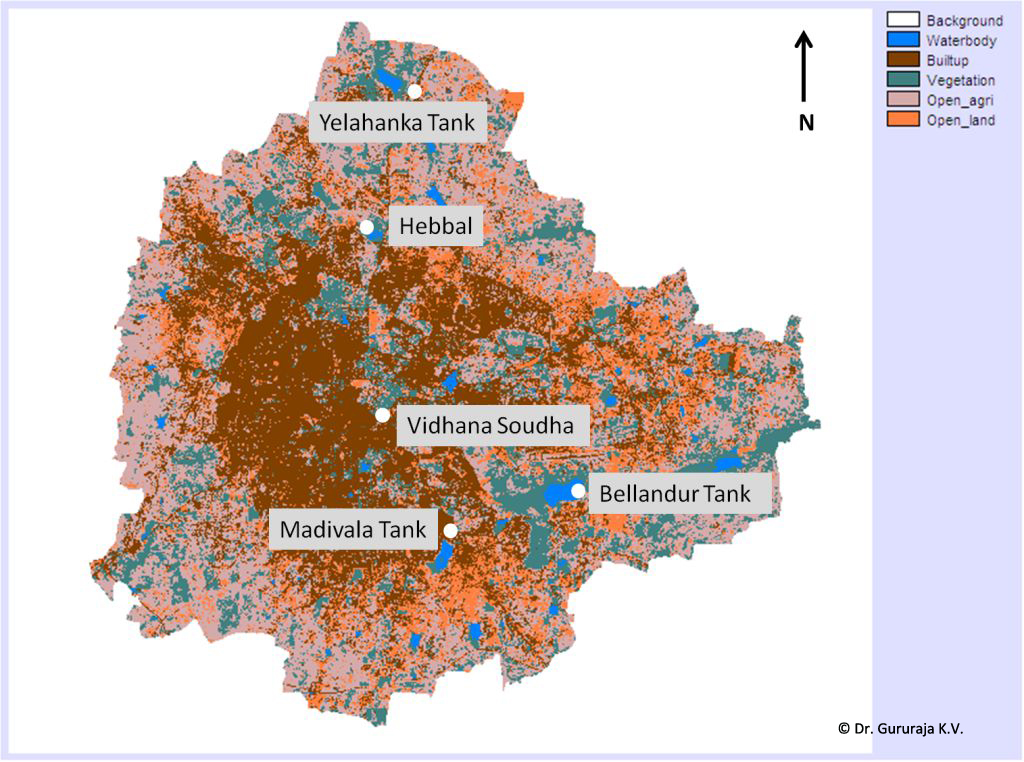

Bangalore BBMP Boundary

With urbanisation, we have more roads being laid out. Roads kill wildlife and frogs in particular, as they are slow movers. Added to this, vehicle noise renders calls inaudible. The cacophony we hear of frogs is the act of males vocalising to attract mates. If this is not audible to the female, the population begins to decline. Urbanisation also means gardens and sprawling “English countryside” type of lawns are synonymous with it in today’s world. Such habitats neither support biodiversity nor are they of any particular utility, as people are not allowed to trample this carefully manicured lawn. Many frogs live in leaf litter and need bare earth to burrow into. Any leaf litter that collects on these lawns is gathered and burned. Fires clear everything in their path and it is the greatest threat to a lot of fauna like centipedes, millipedes, frogs and snakes.

Lake encroachment

While a majority of water bodies and lakes are gone, a handful of those that remain are in a derelict state. With sewage flowing into the water, the nutrients increase causing ‘Eutrophication’ and heavy metal pollution. Larger catchment areas are modified leading to reduced water flow. Many “well-meaning” human interventions cause unforeseen damage to frogs; “Engineering solutions” to develop and maintain tanks is a case in point. Here, the shoreline is dug up with a land mover. The mud is then dumped on the bund and around the shore, increasing the height. A walking track is later built on it and is transfixed with bright lights. The resulting slope or embankment is pitched with boulder stones. All this may appear aesthetically pleasing, but, stone pitching will plunder the important ecological components of the tank such as the natural muddy slope, vegetation cover and leaf litter. Almost all frogs found in cities live on such natural shorelines. Many other frogs move from the water to surrounding areas. When the embankment is lined with stones and raised above the water level, it creates a physical barrier to movement.

The embankment of the Lalbagh lake pitched with boulder stones

The value of what we are losing?

Recent surveys by amphibian biologists in the city ring alarm bells. Of over 17 species that existed just a decade ago, over 90% of them can no longer be found within the city limits (Seshadri and Gururaja 2012). Wetlands are devoid of frogs. The nights are dark and silent. One has to reach the outskirts to see or even hear a frog. I myself have not seen a frog in my neighbourhood in the last decade.

Frogs and toads are primarily insectivores and they are traditionally believed to keep pests like mosquitoes under control by feeding on them. They act as conveyer belts in our ecosystem, by means of which energy flows from the insect group to the vertebrate group, thus forming a vital ecological link in the food chain. Modified habitats also affect the food resources that exist for frogs. If frogs and toads are wiped out of the globe, the world will perhaps be full of insects.

Every day, we are becoming poorer. We no longer spend our evenings on the house verandah, listening to the chorus of frogs. We no longer want gardens in our houses but want more space to park our vehicles. We no longer care for anything that we do not see easily. We do not see them, thus we do not think of them. As for the frogs, out of sight is not merely out of mind, it is out of our existence.

Cities are meant to develop, there is no denying that. However, we ought to use a little more ‘ecological sense’ when designing our cities and modifying our landscapes. Perhaps, it is time we let frogs leap closer to our hearts by recognising and accepting that their presence adds more than just ambience to our urbanised lives. We do them no favours by enabling them to live. They will most certainly outlive us, only if we are careful and considerate enough.

Over the few years, several attempts are being made to popularize frogs in our cities. The ‘Bangalore’s Frogs at Risk!’ poster by Seshadri K.S., Krishna M.B. and Sunil Kumar M., 2012, is being distributed free of charge in Bangalore. See the poster at www.sanctuaryasia.com.

A Pictorial field guide to the Frogs and Toads of Western Ghats by Gururaja. K. V is also available. The same book is available as Frog Find- a free Android App on the Google store. To view the poster click here.

Literature Cited

Bickford D., Howard S.D., Ng D.J.J. & Sheridan J.A. 2010. Impacts of climate change on the amphibians and reptiles of Southeast Asia. Biodiversity and Conservation 19:1043-1062.

Karthikeyan, S. 1999. The Fauna of Bangalore. Bangalore: World Wide Fund for Nature-India. 48 p.

Seshadri. K. S and Gururaja. K. V. 2012. Anuran Amphibians of Bangalore Metropolitan City.Poster at the Conference of Parties, Hyderabad, India.

Instagram

junglelodgesjlr